James Barrett and Robin Forster

- James Barrett and Robin Forster –Trading in Futures - Press release

- Visible Secrets: An Essay on AIDS and Seeing - Simon Watney

Rear Window Publications

1992 © Simon Watney

“The perception of death in life does not have the same function in the nineteenth century as at the Renaissance… death left its old tragic heaven and became the lyrical core of man: his invisible truth, his visible secret.” Michel Foucault, The Birth of the Clinic, Vintage Books, New York, 1975, p. 172.

By the end of July 1992, there had been 6,140 cases of AIDS reported in the United Kingdom, with a further 17,868 reported cases of HIV infection (Public Health Laboratory Service, Quarterly AIDS and HIV Figures, 27 July 1992). It thus follows that most people in Britain have not knowingly met anyone with HIV or AIDS, let alone experienced personal loss as a result of the epidemic. To date, 80& of AIDS cases in Britain have been amongst gay and bisexual men, and direct experience of HIV-related illness is increasingly widespread in the gay communities. In such circumstances representation plays a special and significant role in defining the “look” of people living with HIV or AIDS. This epidemic is uniquely mediated by the mass media, who carefully select and calibrate how AIDS is depicted, and hence how it is seen, thought about, taken seriously, or ignored.

Much attention has been paid to the ways in which people living with AIDS have been represented as “AIDS victim,” passive and powerless. As the epidemic worsens, such conflicts are likely to increase, not least because AIDS is still widely presented in the media as a subject of scandal. And HIV or AIDS diagnosis is widely read as evidence of guilty secrets, usually of a sexual nature. In this manner, people can be blamed for their own illness, which they are held to have chosen, or brought on themselves. This is only possible when people with HIV and AIDS are seen as essentially different from the rest of the population, and if that difference plays a role in the way that most people regard themselves.

AIDS is thus often presented as a form of didactic spectacle, supposedly illustrating the “dangers” of homosexuality, “promiscuity,” prostitution and so on. At the same time, anxieties are aroused concerning the look of these “dangerous” people, who must be unmasked and clearly identified. Hence the widespread tendency of photographers and others to depict AIDS at its most visible, either through symptoms of extreme physical wasting and emaciation, or in external cancers and other visible conditions. Such imagery is essentially sadistic in so far as it encourages us to consider such symptoms as punishments or deserved consequences for culpable actions (See Simon Watney, “The Spectacle of AIDS,” October, No. 42, MIT Cambridge, Winter 1987, pp. 71-86). It requires pain, and is intended to shock.

At the same time, gay men are constantly aware of the epidemic from the very different perspective of concerns about ourselves and our loved ones. Indeed the image of the gay man anxiously studying his face in a mirror has become of the central, emblematic images of the epidemic. Yet even this image is not to be trusted, at least not in terms in which it is generally proffered. For it is usually taken to imply that all gay men are ceaselessly checking themselves for “tell-tale signs” of illness. The reality is more complex. The homophobic gaze regards AIDS as evidence of deviance and depravity, as a warning, and as a source of danger and pollution Gay men, on the contrary, regards AIDS in the register of tragedy. We live cheek by jowl with HIV all the time, and there can be no predicting how individuals will respond over time either to the stress of not knowing their own HIV status, or to the possible stress of knowing it.

HIV is an extremely slow illness, hedged round with considerable doubts and uncertainties. Rates of progression vary greatly, as do life-expectancy rates. We feel far more confidence about prevention than about services or treatment issues. When we examine ourselves and one another we do not generally see danger, but doubt. Nothing could be more complex than a gay man’s physical examination of his body at a time when 1 in 5 gay men attending London based Genito-Urinary Medicine clinics for HIV tests discover they are positive. Many will have learned to adjust to the new world of AIDS, and have more or less painfully accommodated themselves to living with uncertainty concerning their own HIV status. Others repeatedly go for tests. Some retreat into fearful celibacy. The great majority explore and enjoy Safer Sex.

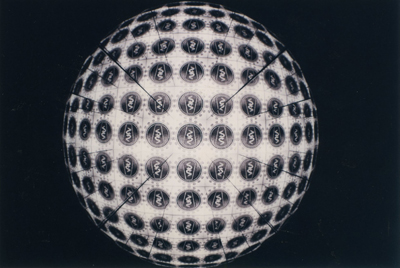

Yet only rarely does the public representation of AIDS register anything of the actual complex realities of the epidemic. Hence it is hardly surprising that representation has become a site of intense contestation between different groups of people with different and mutually exclusive agendas. It is thus highly significant that James Barrett and Robin Forster are both deeply involved in AIDS work, since their response to the epidemic as artists is so massively informed by their direct lived experience, personally and professionally. Rejecting overly crude didactism, their work draws attention to the deepest questions of visibility and invisibility in the AIDS crisis. Looking down into their magical plinths we see geometric planets of flesh, themselves analogous to the testicles which the flesh envelopes. And we also see ourselves, multiplied countless times, looking and being looked at.

These are sculptures that invite us to consider the body as an ensemble of parts, each of which may be made visible under different conditions, in relation to different institutions, and in different registers of signification. Thus the surfaces of the body may be viewed from the medical perspective of dermatology, or in the register of pornography. Isolated and enlarged, skin lacks features or individuality. It is simply a membrane, the housing of the body, as well as the site of our most intense relations with other bodies, other surfaces. Skin is the site of our perceptions of others and ourselves, as well as the site of projection and transference. Furthermore, like other beasts, we can be skinned. Our protective exterior can be removed, and the body filly revealed in the nakedness of pathological medicine, stripped of identity, removed from the field of desire.

This is art about fear, both realistic and projective. It invites us to pause to consider the diagnostic element in the field of vision, the question we ceaselessly bring to seeing alongside our complex de-codings of class, gender, age, or race. This level of fantasy may engage very powerful unconscious motives in an epidemic, especially when questions of physical health are elided with our looks. In such circumstances, seeing involves a heavily defensive component, as we seek reassurance of our own appearance, and that of others. These are periscopes that re-stage inside themselves a complex “penal theatre of anatomy” (Francis Baker, The Tremulous Private Body: Essays on Subjection, Methuen, London, 1984, p. 84). Here against the opaque, pink screens of genital flesh we may begin to trace not the physical symptoms of AIDS, but the psychic symptoms of homophobic anxiety. No “answers” are provided, for none is available. There is only the vertiginous sense of conflict in our attempts to hold the body in a visual economy of life and health. We stand on the edge of vision out of control.

Simon Watney is an art historian, author, critic and well-known AIDS activist who has written for Artforum, Frieze, October and New York’s Village Voice. His 8th book, Practices of Freedom: Selected Writings on HIV and AIDS will be published in 1993 by Rivers Oram Press.